Sorry, I know this is really long, but the reading was

really long and then the documentary was really long… so this ended up being

really long when I finished putting my thoughts to paper. If others didn’t have

time to finish watching the film, I have a pretty good summary below that might

help.

I finished watching the documentary about Paul

Robeson, “Here I Stand,” and I found myself going back and re-watching different

segments several times. As a “Jersey Girl,” I have grown up with a great

understanding and appreciation for Paul Robeson as a great bass vocalist, Broadway

actor and artist who played Othello in the longest run of any Shakespeare play

on Broadway, film star to play more than

just an Uncle Tom character, as well as an individual who shattered glass

ceilings in 1915-1919 by being named Phi Beta Kappa his Junior Year and

greatest oralist, as well as all American athlete, lettering in twelve sports

at Rutgers, but I never truly understood his contributions to civil rights for

the poor and oppressed and political activism for the unionized working class until

I watched this documentary.

Our HB Reading, “Robeson: crossing over,” discusses in

detail why Robeson was a successful cross-over artist—appealing to both black

and white audiences from all walks of life—from the 1920s through World War II. Dyer explains that this cross-over reflected

Robeson’s ability to master two major stereotypes of blacks—Magic Negro/Uncle Tom

and atavism (brute-beast primitive sexuality and physicality). On the one hand,

Robeson’s good looks and large sexual body with its clear potential for great physical

strength, which is matched by his powerful vocal voice, were prominently

featured time and time again in films and other performances. Yet, by adopting

an Uncle Tom-like wisdom and physical stillness that is contained and restrained—defined

almost as a “sculptured stillness”—white cultures could embrace the “almost unbearable”

pathos found in humbling such a powerful man. At the same time, black audiences found

reality in his voice, even without any physical action, and with white audiences could similarly

empathize with Robeson’s soft, careful actual delivery of speech and song that expressed

the sorrow and spirituality of his people. Robeson was also a model of black potential and success, and he became “an emblem of racial

suffering” (126).

In thinking about Robeson films that I have seen, the miscegenation

scene in “Show Boat” that Dyer discusses, e.g. when the Sheriff comes to arrest Julie and Steve for

inter-racial marriage, sticks out the most for me re: the power of Robeson’s "still" performance. However, while I agree that stillness might be a device for a "Magic Negro" who helps the white man see justice and injustice, I do not think stillness is a weak/feminine white quality as Dyers suggests. Instead, for me, when Robeson stands alone above in the galley—ironically, the place

where segregated blacks had to sit to watch the show, you almost feel as if he

is God, judging mankind for its cruelty to blacks. I was always moved by this

scene and captivated by Robeson’s deep bass voice and calmness. I know Dyer saw this stillness as subjugation, but for me it was powerful and commanding, invoking my sense of injustice and shame for how a white America treated these citizens who helped build our country. Robeson's performance also reminded me today of many of the roles James Earl Jones plays.

Of course,

white society dictated the terms of America’s acceptance of this “exceptional”

black man. Robeson was most appealing as a cross-over artist when he played the

on-looker, observer or conscience of the white man for the black man’s sorrow

and injustices. But, when Robeson no longer became the object of the gaze and a still statue but an active, often angry, black man, according to Dyer, his cross-over appeal ended. The documentary explores the rise of this cross-over

appeal and, even more dramatically, the end of this appeal, supporting Dyer's argument.

In the documentary, although emblematic of racism, Robeson was portrayed early in his career not as the normal black but the “exceptional,” model negro—educated, wealthy, well-spoken, handsome, athletic, and patriotic. In World War II, Robeson sold war bonds, performed patriotic concerts and spoke passionately about his belief in America and the black’s responsibility to fight. This changed in 1946—just one year after WWII when thousands of blacks had died fighting for a segregated America, 46 blacks were lynched in the South. When Robeson met with Truman, he was told it was not politically expedient to do anything about that right now. Outraged that he had encouraged blacks to fight for a country that continued to subjugate them, he turned to the power of his words to encourage blacks to fight back for their civil rights. However, America's white and black community—even the NAACP—turned on him as “Red Fear” of Communism spread through the nation. A socialist, not a Communist, Robeson refused to be cowered by the Committee or anyone who sought to deny him his right to practice free speech or free association.

In the documentary, although emblematic of racism, Robeson was portrayed early in his career not as the normal black but the “exceptional,” model negro—educated, wealthy, well-spoken, handsome, athletic, and patriotic. In World War II, Robeson sold war bonds, performed patriotic concerts and spoke passionately about his belief in America and the black’s responsibility to fight. This changed in 1946—just one year after WWII when thousands of blacks had died fighting for a segregated America, 46 blacks were lynched in the South. When Robeson met with Truman, he was told it was not politically expedient to do anything about that right now. Outraged that he had encouraged blacks to fight for a country that continued to subjugate them, he turned to the power of his words to encourage blacks to fight back for their civil rights. However, America's white and black community—even the NAACP—turned on him as “Red Fear” of Communism spread through the nation. A socialist, not a Communist, Robeson refused to be cowered by the Committee or anyone who sought to deny him his right to practice free speech or free association.

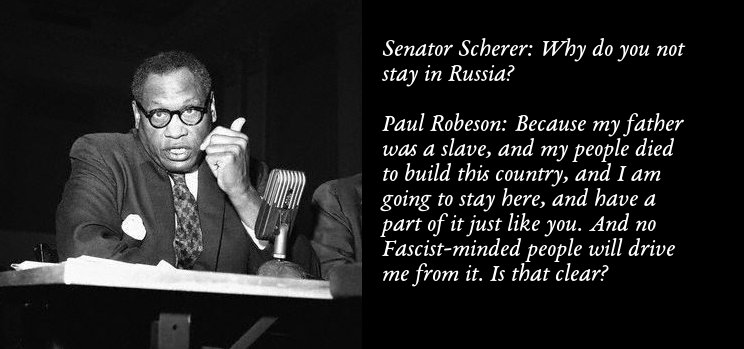

Robeson spent his life fighting for civil rights of blacks and the rights of union workers. Recognized as one of the ten most important people in the world (not black men, but all people), his words were important. But, the words I found most moving by Robeson in the film were those he spoke to the House Un-American Activities Committee when subpoenaed to testify for his continued defense of Soviet Communism. When asked why he didn’t stay in Russia, his response was defiant, strong and crystal clear: “Because my father was a slave and my people died to build this country, and, I am going to stay here, and have a part of it just like you. And no Fascist-minded people will drive me from it. Is that clear?”

After a final attempt to rally people for peace with the Soviet Union at a violent concert at Peekskill (#2), the FBI and the Committee proceeded to destroy him, taking away his passport, and preventing him from performing anywhere—association with Robeson was deemed to be associating with a Communist and the FBI evidently conducted surveillance of his activities and even took the license plate numbers of anyone who attended even a church where he sang. The white press erased him from history for almost 20 years. Yet, convinced the enemy of discrimination and persecution persists in America, he never regretted sacrificing the privileges of the self for the rights of others. In 1958, with the end of the Red Scare, he was welcomed back into America's arms with a sold-out concert at Carnegie Hall.

What I found perplexing was his relationship not with

Lenin’s Russia—which I discovered on the internet had been a sanctuary for

thousands of African-American intellectuals who were highly valued and paid

well to relocate in the 1920s and part of the 1930s—but with Stalin’s brutal

dictatorship. Stalin actually exiled the thousands of African-Americans who had prospered under the former regime. He also and murdered intellectuals and

artists who believed in socialism and free thought, including Robeson’s Jewish

intellectual friend Itzik Ferrer. In a June 1949 Concert at Moscow's Tchaikovsky

Hall, Robeson had discovered these atrocities against humanity and sang as his encore “Zog nit Keynmol", the defiant "Song

of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Yet, when he returned to America, he insisted

that he saw no purges.

Robeson’s son explained that his father weighed the evils of Communism versus the 300-year-old persecution of blacks in America that persisted even after blacks courageously fought in World War II--and he came out in favor of supporting anything that was closer to socialism than what was found in America. Yet, I found it curious that someone who so strongly believed in fighting injustices where he saw them did not fight this one, too. I just don't know how you place a hierarchy on evil in any form.

Robeson’s son explained that his father weighed the evils of Communism versus the 300-year-old persecution of blacks in America that persisted even after blacks courageously fought in World War II--and he came out in favor of supporting anything that was closer to socialism than what was found in America. Yet, I found it curious that someone who so strongly believed in fighting injustices where he saw them did not fight this one, too. I just don't know how you place a hierarchy on evil in any form.

In reconciling Dyer’s book with the documentary, I would also note that I completely disagree with Dyer to the extent he agrees with Cruse or Bogle that Robeson was for himself first and for his people and civil rights only when it promoted his own cause (66). Robeson fought for civil rights his entire life—first by trying to work within the white cultural system to show racial equality (or even superiority) by shattering barriers and walls in athletics, education, law (Columbia law grad), and then in the arts—by eventually refusing parts that put blacks in primitive stereotypical roles, changing the lyrics of “Old Man River” (refusing to sing the word ‘nigger’), playing Othello with a cast of white actors—a part where he must kiss, strangle and later kill his white wife without inflaming white audiences, and the many other examples shown in the film. Then, when he felt that his country would never stop subjugating and lynching blacks, he used his power to voice his outrage—so much to his detriment, he completely lost any ability to earn an income for almost 20 years. If those are the actions of someone self-centered, then we need a great more self-centered people in this country to speak and stand up.

No comments:

Post a Comment